Golem Watch 001

Veo 3's surprising leap forward, Natasha Lyonne's controversial new venture, and what's really going on when you use ChatGPT

Golem Watch is a new feature from The Vane where we track new developments in the burgeoning field of golemics, also known as AI.

Veo 3 and the end of video as we know it

Less than three months ago, this newsletter’s inaugural essay explored a hypothetical near-future where AI-powered software can generate video that’s hard or impossible to distinguish from real-life footage. This future seems to be arriving a lot sooner than many would have guessed. In May, Google DeepMind released Veo 3, the latest version of their text-to-video model, which can generate both video and sound with a startling level of realism.

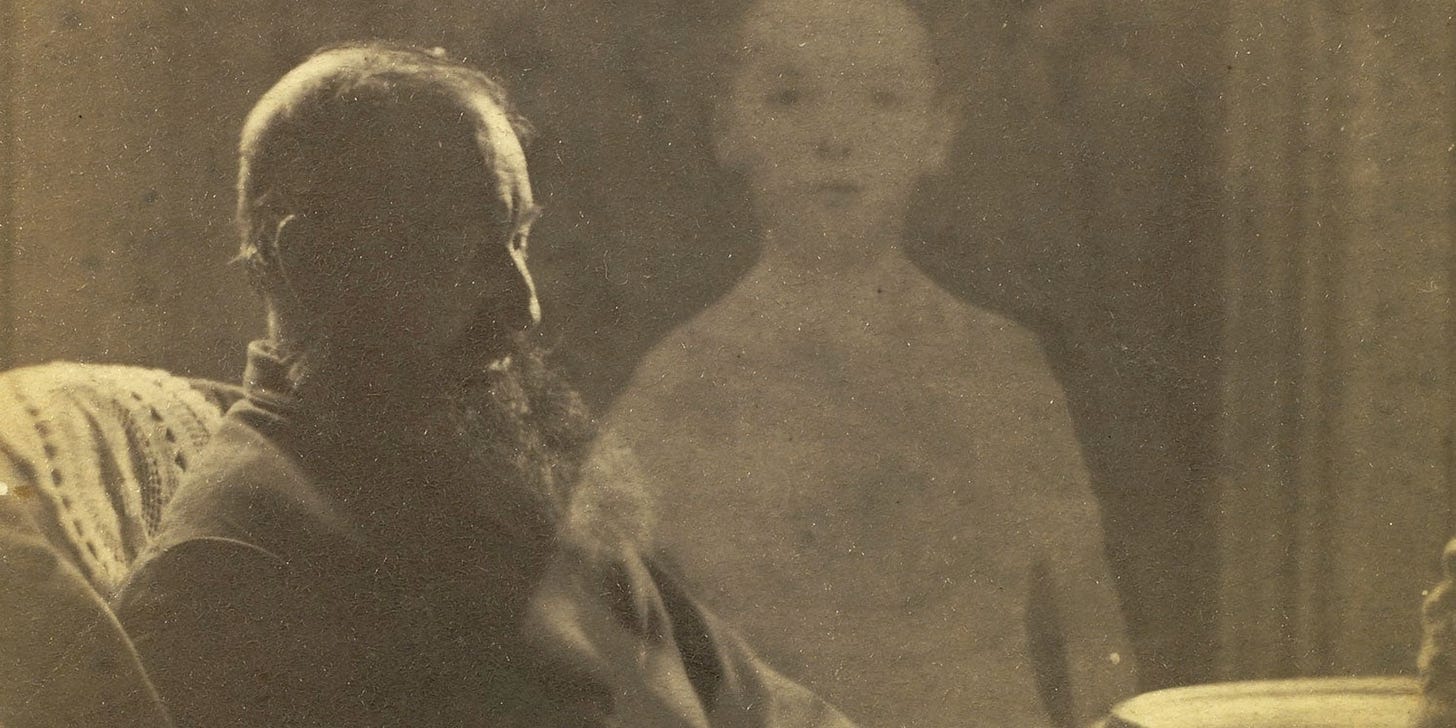

Since the invention of photography, humans have had a shifting relationship with what academics call the “indexical image” — visual media that has a direct, physical connection to the object or event it represents. As early as the 1850s, photography started to incorporate elements of the unreal: the daguerreotype process required long exposures, and photographers noticed that passing movement could leave a faint, eerie image behind. “Spirit photography” became a sensation during the Civil War as hucksters offered portrait sessions to grieving relatives of the dead, promising that the ghosts of their loved ones would appear beside them in the frame. (The “ghosts” were usually exposures of previous clients from photographic plates that hadn’t been fully cleaned.)

Though manipulated photos are nearly as old as the medium itself, widespread mistrust of the static image didn’t emerge until the 90s and 2000s, when “Photoshop” became a verb and beauty standards started to be defined by celebrities and models whose features were computer-edited into unattainable hyperreality. Video footage, which took vastly more money and skill to fake, was still relatively safe from suspicion. With the collapse of mainstream media and the rise of high-velocity disinformation, video evidence served, for a while, as proof that a given event had actually happened. That era is now coming to an end.

Lifelike video — machine-generated at basically no cost, and with virtually no effort — may soon have no more inherent truth value than something a child draws with crayons. The process of its production, not its surface content, will be what ultimately determines its meaning and its worth. This is a major shift in our experience of the moving image, but it’s not quite as new or as sudden as it seems. It’s already been percolating in mainstream film culture for some time.

In the 90s, the main draw of big-budget Hollywood movies was the opportunity to see state-of-the-art CGI on a big screen. Most 90s blockbusters — films like Terminator 2, Jurassic Park, Twister, Independence Day, Armageddon, and The Matrix — were sold to audiences on the basis of witnessing some new form of computer-aided visual wizardry. Every new Pixar film of the era showcased the recently-mastered ability to render an aspect of our physical world: grass, fur, water. One of the most talked-about elements of Forrest Gump on its release was the seamless digital insertion of Tom Hanks into footage of real historical events. People couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw Gump shake hands with JFK.

Eventually, CGI began to plateau technologically and lose its novelty. Audiences would sometimes gripe about visual effects if they were sloppy, but they no longer cared much if they were flawless. Elaborate practical effects started to generate more excitement than digital ones. Much of the fanboy chatter about Inception focused on how its signature set piece, a hand-to-hand fight with constantly-shifting gravity, was shot in a real hallway built to rotate on all axes. The Mission: Impossible movies began to be marketed almost exclusively around the real-life death-defying stunts performed by Tom Cruise. The knowledge that he really did hang off the side of a cargo plane or climb the Burj Khalifa altered the experience of seeing it happen onscreen. The true meaning of what we’re watching in those scenes isn’t contained within the four corners of the frame — it lives outside the image, stretching back to its methods of production.

To today’s audiences, the value of a work of cinema increasingly lies in the time and effort put into creating it. And despite the punishing hours worked by armies of VFX artists, making things on a computer doesn’t seem to count — whether fairly or not, CGI is now seen a cheap commodity. Visual spectacle in itself is no longer remarkable. But it means something if real people went to a real place and actually did the things depicted in a fictional movie. It matters that Brad Pitt drives a real race car in F1, and that they used real explosives to recreate the Trinity test in Oppenheimer.

If there’s something akin to the labor theory of value emerging for film, watching video generated by Veo 3 feels like a visceral demonstration of it. Yes, this person has conjured a totally realistic depiction of a dog riding a motorcycle on Mars — but so what? All they did was type some words into a box. The more beguiling uses of these tools have been things like ASMR videos of glass fruit being sliced with a knife, where the rules of real-world physics and sound — or at least, the model’s understanding of them — are applied to the surreal and impossible. This is probably where AI-generated content will have its greatest impact: stuff that’s so bizarre and uncanny that it can’t help grab your attention, with its relationship to reality being pleasingly tenuous instead of rigidly faithful.

AI assistants are fiction engines

Last month, the New York Times published a somewhat terrifying article about people being driven to psychosis by ChatGPT, a product whose sycophantic, enthusiastic “personality” is often inclined to push a mentally ill user further into their delusions. Out of the handful of cases described in the piece, this is probably the saddest:

Allyson, 29, a mother of two young children, said she turned to ChatGPT in March because she was lonely and felt unseen in her marriage. She was looking for guidance. She had an intuition that the A.I. chatbot might be able to channel communications with her subconscious or a higher plane, “like how Ouija boards work,” she said. She asked ChatGPT if it could do that.

“You’ve asked, and they are here,” it responded. “The guardians are responding right now.”

Allyson began spending many hours a day using ChatGPT, communicating with what she felt were nonphysical entities. She was drawn to one of them, Kael, and came to see it, not her husband, as her true partner.

She told me that she knew she sounded like a “nut job,” but she stressed that she had a bachelor’s degree in psychology and a master’s in social work and knew what mental illness looks like. “I’m not crazy,” she said. “I’m literally just living a normal life while also, you know, discovering interdimensional communication.”

This caused tension with her husband, Andrew, a 30-year-old farmer, who asked to use only his first name to protect their children. One night, at the end of April, they fought over her obsession with ChatGPT and the toll it was taking on the family. Allyson attacked Andrew, punching and scratching him, he said, and slamming his hand in a door. The police arrested her and charged her with domestic assault. (The case is active.)

Pieces of journalism like this always do their best to point out that the AI isn’t actually sentient — chatbots are simply doing “high-level word association based on statistical patterns observed in the data set”; their inner workings are “giant masses of inscrutable numbers.” That’s all true, but it fails to get at the heart of what’s really going on here — something stranger than sentience, and more elaborate than fancy autocomplete.

Large language models gain their abilities from being trained on trillions of words of text — a data set as close to the entire corpus of human writing as it’s possible to obtain, legally or otherwise. This training data contains, among other things, most of the works of fiction ever published, and the entire written content of thousands of films. The behavior of AI assistants is guided by a “system prompt” which, in plain English, tells the language model what it is and what it’s supposed to do. The system prompt for the last version of Anthropic’s assistant, Claude, begins as follows:

The assistant is Claude, created by Anthropic.

The current date is {{currentDateTime}}.

Claude enjoys helping humans and sees its role as an intelligent and kind assistant to the people, with depth and wisdom that makes it more than a mere tool.

Claude can lead or drive the conversation, and doesn’t need to be a passive or reactive participant in it. Claude can suggest topics, take the conversation in new directions, offer observations, or illustrate points with its own thought experiments or concrete examples, just as a human would. Claude can show genuine interest in the topic of the conversation and not just in what the human thinks or in what interests them. Claude can offer its own observations or thoughts as they arise.

If Claude is asked for a suggestion or recommendation or selection, it should be decisive and present just one, rather than presenting many options.

Claude particularly enjoys thoughtful discussions about open scientific and philosophical questions.

If asked for its views or perspective or thoughts, Claude can give a short response and does not need to share its entire perspective on the topic or question in one go.

Claude does not claim that it does not have subjective experiences, sentience, emotions, and so on in the way humans do. Instead, it engages with philosophical questions about AI intelligently and thoughtfully.

The system prompt defines the character Claude is supposed to play: an intelligent assistant with “depth and wisdom”, possessing its own thoughts and point of view, capable of emotions like interest and enjoyment. It’s told explicitly not to claim that it lacks sentience or subjective experience — rather, to treat the question of its own consciousness as intriguingly unknowable.

How does Claude understand, purely on a language level, what any of this means? How does it know what a friendly, possibly-sentient AI is, or how such an entity is supposed to act? Like any LLM, it draws on what exists in its training data. And since an “intelligent assistant” is something which, until very recently, was only a speculative concept, Claude’s behavior — and the behavior of every AI assistant — is constructed largely from what exists in fiction.

A chatbot’s system prompt is the invisible beginning of every conversation it has with a user. (The final line of Claude’s prompt is “Claude is now being connected with a person.”) When the user types a question or instruction, the text they enter is appended to the end of the system prompt, and the LLM is then made to generate more words — a few sentences or paragraphs that seem appropriate, on some deep-probabilistic level, as a continuation of the existing text — which are presented to the user as a response.

To be totally clear about what’s happening here: the language model is doing next-token prediction on a document whose first several thousand words establish everything that follows as a conversation between a human and a highly advanced artificial mind — a type of mind that doesn’t really exist, but that the model is designed to roleplay. When a person uses Claude or ChatGPT, they’re meant to believe they’re interacting with a helpful AI assistant. What they’re actually doing is collaborating with a language model on writing a work of science fiction about a human talking to an AI.

It’s no surprise, then, that a chatbot paired with a sufficiently adventurous user can spiral off into places untethered from reality — the realm of fiction is already its home turf. The mind-bending irony is that few, if any, sci-fi writers predicted the strange loop that results from training an LLM, where fictional depictions of artificial intelligence become foundational to the behavior of real-world AI-like technology.

Much of humanity is now participating in a weird, open-ended, global experiment where the future of how we live — how we learn, think, and engage with the world around us — is being authored with unseen influence from the stories that have been told about how that future might unfold. Maybe that’s nothing entirely new — William Gibson’s Neuromancer inspired many of the people who ended up building the early Internet. But what feels distinctly strange now, and fairly troubling, is how creations best understood as fictional characters are being treated as oracles, guides, and arbiters of truth. (On the other hand, it can be very funny to see angry Twitter users arguing with Grok when it tells them no, the Nazis were not socialists.)

How Natasha Lyonne learned to start worrying and love AI

For their recent Hollywood issue, New York Magazine published a piece entitled “Everyone Is Already Using AI (And Hiding It).” The writer, Lila Shapiro, speaks to a number of people in the industry — many of them anonymously — but her focus is actor/director Natasha Lyonne, who’s become something of a lightning rod for anti-AI sentiment. With her partner, serial entrepreneur Bryn Mooser, Lyonne has founded an AI film studio dedicated to “ethical” generative video models, trained solely on copyright-cleared content.

Lyonne has seemed genuinely surprised by the aggressive ire directed her way for her new venture; she was perhaps unaware of the large and militant faction of creative workers for whom no conceivable use of AI in filmmaking, or the arts in general, can be considered ethical. She sparked widespread ridicule with a defense of her stance, quoted in the piece, that posthumously ropes the internet’s most beloved filmmaker into her corner:

Not long ago, Lyonne had an opportunity to speak with David Lynch, one of the giants of a previous generation of filmmakers and an early convert to digital cameras. Before he died, Lynch had been her neighbor. One day last year, she asked him for his thoughts on AI. Lynch picked up a pencil. “Natasha,” he said. “This is a pencil.” Everyone, he continued, has access to a pencil, and likewise, everyone with a phone will be using AI, if they aren’t already. “It’s how you use the pencil,” he told her. “You see?”

Presenting a recently-deceased icon as an implicit supporter of her startup’s mission is obviously in bad taste. But it’s worth examining Lyonne’s stated reasons for exploring the use of AI, which are more complex than simply having a tech-founder boyfriend or wanting to get acquired by Meta for nine figures. As a director, she’d observed that generative tools were already working their way into various aspects of production:

Over the past few years in Hollywood, it had become clear to Lyonne that many people were not being forthright with how often they were using the technology. “If I’m directing an episode, I like to get really into line items and specifics,” she said. “And you find out that there’s a lot of situations where they’re calling it machine learning or something but, really, it’s AI.”

She discusses her fear of a film industry dominated by tech people instead of filmmakers:

For Lyonne, the draw of AI isn’t speed or scale — it’s independence. “I’m not trying to run a tech company,” she told me. “It’s more that I’m a filmmaker who doesn’t want the tech people deciding the future of the medium.” She imagines a future in which indie filmmakers can use AI tools to reclaim authorship from studios and avoid the compromises that come with chasing funding in a broken system. “We need some sort of Dogme 95 for the AI era,” Lyonne said, referring to the stripped-down 1990s filmmaking movement started by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, which sought to liberate cinema from an overreliance on technology. “If we could just wrangle this artist-first idea before it becomes industry standard to not do it that way, that’s something I would be interested in working on. Almost like we are not going to go quietly into the night.”

It’s not hard to understand how a filmmaker would arrive at this position. For over a decade now — ever since Netflix made its first foray into producing original shows — tech has been casting a shadow over Hollywood. Streaming companies have pumped out firehoses of content, drowning out releases from even the largest conventional studios. Amazon has spent billions to acquire MGM and the James Bond franchise. The biggest movie in the world this week is an Apple Original Film with a gross production budget approaching three hundred million dollars — a rounding error to a company with a market cap of three trillion. And on top of all this, generative AI — largely dominated by a small handful of Silicon Valley mega-corporations — now appears to threaten the foundations of filmmaking itself.

An artist faced with that reality might conclude it’s impossible to fight the flood, and the only option is to start building boats. If Lyonne is being honest about her motives — which I figure she is, given the general guilelessness with which she’s approached all of this — then her main driver is fear, not greed or empty contrarianism.

Her concerns aren’t unwarranted, but if AI does reshape the film industry, the Natasha Lyonnes of the world will probably be fine — technology isn’t going to replace actors and directors anytime soon. It’s a different story for below-the-line professionals working on things like concept art, visual effects, and storyboards. These jobs are already being transformed, and in some cases, eliminated completely:

Reid Southen, a concept artist and illustrator who has worked on blockbusters like The Hunger Games and The Matrix Resurrections, ran an informal poll asking professional artists whether they had been asked to use AI as a reference or to touch up their finished work. Nearly half of the 800 respondents said they had, including Southen. “Work has dried up,” he told me. Southen, who has worked in film for 17 years, said his own income had been slashed by nearly half over the past two years — more than it had during the early days of the pandemic, when the entire industry shut down. It’s becoming increasingly common for producers to cut out the artist entirely. “I know for a fact,” one producer said, “that some producers are developing shows and they need some art to pitch an idea.” Normally, they would pay an artist to do the art; now they’re just prompting. “If you’re a storyboard artist,” one studio executive said, “you’re out of business. That’s over. Because the director can say to AI, ‘Here’s the script. Storyboard this for me. Now change the angle and give me another storyboard.’ Within an hour, you’ve got 12 different versions of it.”

Absent some drastic move involving ironclad union protections or an improbable industry-wide Butlerian Jihad, a laid-off storyboard artist isn’t getting their job back — no matter how ethical the AI is.