The Future of Human Cinema

Will filmmaking survive AI?

Two weeks ago, a team of AI researchers published a forecast of the next five years of progress in the field. They envision a swift takeoff toward artificial superintelligence in 2027, after which their scenario branches into two paths: a slowdown where the rapidly evolving AI is reined in to ensure its alignment with human goals, and an accelerating race between China and the United States toward a technological singularity. In the latter scenario, the super-AIs built by the two rival nations merge into a single entity that casually exterminates humanity, blankets the earth’s surface with solar panels and automated factories, and begins colonizing the galaxy with robots. In the “slowdown” ending, the better-aligned AIs grow into a friendly superintelligence that cures most diseases, eradicates poverty, and makes war obsolete. All of this happens by 2030.

It’s an engaging piece of science fiction, but as a prediction of the future, it relies on some questionable assumptions, the most load-bearing of which is that present-day AI sits at the bottom of an exponential intelligence curve headed straight to infinity. The real arc is looking more S-shaped: despite breathless hype and frantic investment, the basic capabilities of large language models have been leveling off. Still, those capabilities are significant, and we’re only starting to work through their implications.

OpenAI recently unveiled a new image generator that’s almost frighteningly competent in its ability to follow detailed prompts to the letter. Video generation is in a somewhat less advanced state — models are achieving near-photorealism for static frames, but since they lack a true understanding of real-world physics, they struggle with complex motion and scene consistency. Progress has been steady and there are countless well-funded companies chasing the grail.

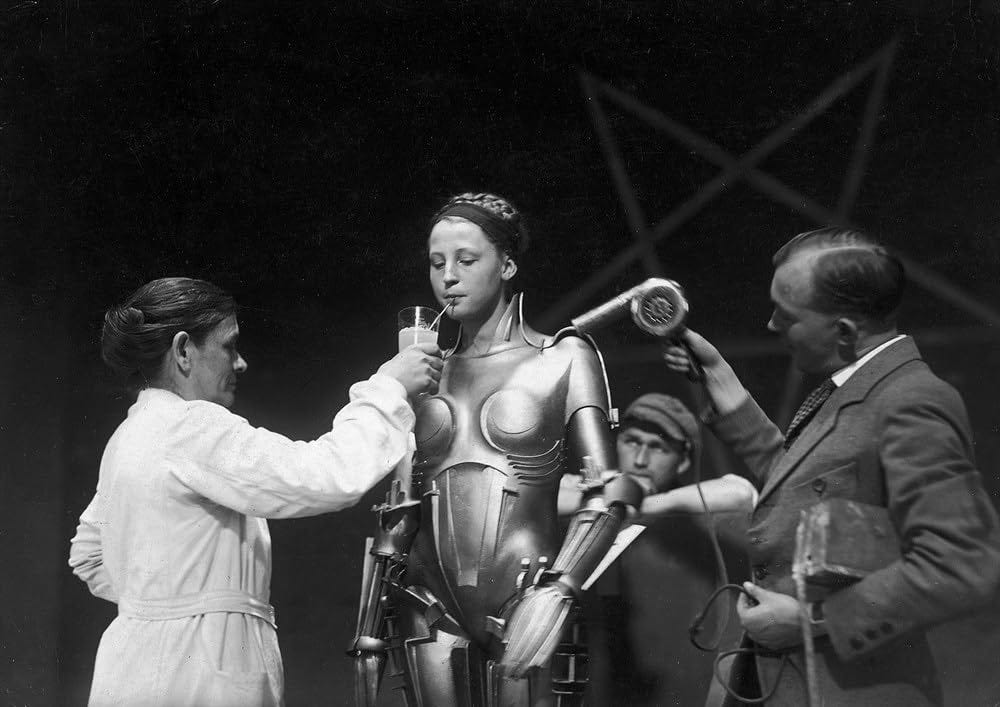

Filmmaking is objectively a pretty strange endeavor. You gather dozens or hundreds of people together to fashion fake environments for actors to perform in, take twenty-four photographs of them per second as they act out the same words and gestures five or ten or fifty times, and then move your complicated arrangements of lights and cameras around and do it all over again from a different angle. You do this for fourteen hours every day. This goes on for weeks or months and generally costs a lot of money. It’s both incredibly tedious and so difficult that it can trigger mental breakdowns for the people involved. Many of these people consider it their reason for existing. They’ll sacrifice everything else in their lives for the chance to do it.

The art of turning dressed-up reality into rectangular moving images is a collaboration between humans and a majestic, infinitely complex, often uncooperative universe. Like photography, cinema leverages the richness of an already-existing world — the physical realm of light, nature, people, and manmade objects — and transforms three-dimensional space into a transmissible piece of human expression. Sometimes the real world can’t provide all the things we want in the frame — say, velociraptors, or Sebulba — so we’ve invented ways to craft images in silicon, using armies of skilled professionals. Even with these tools, the essence of the work has remained the same: actors on a set performing in front of a lens.

It’s not usually necessary to talk about filmmaking in such fundamental terms, but recent developments are forcing the issue. For the first time, it’s becoming possible to obtain realistic footage simply by asking a machine for it. The output is still, in a sense, the product of human labor — it can only exist because the machine has been fed a wealth of human-generated footage and text — but it’s divorced from human hands by trillions of mathematical operations and layers of interpolation. It doesn’t come from reality, and it doesn’t come from a human mind. It comes from a murky third thing that’s trying its best to imitate both of the above.

Right now, the use of AI video generation in commercial filmmaking is mainly held back by two things: technological limitations, and legal/ethical concerns about the use of copyrighted media in training generative models. (You could argue there’s a third factor — social stigma — but it’s probably not strong enough on its own to hold the barricade if the other two hurdles fall.) Let’s imagine that, sometime in the next few years, these issues are solved. Everyone in the world gains access to magical, copyright-compliant software that can reliably create footage of whatever they ask for, with accurate physics, shot-to-shot consistency of characters and environments, and granular control over camera angles and lighting.

Here in 2025, it already seems more likely than not that this technology will soon exist. When it does, is filmmaking as we know it finished? Let’s think it through, starting with the high end of the business.

Congratulations — the year is 2028, and you’ve just been promoted to president of production at Universal Pictures. Your parent company has completed a merger with Warner Bros. Discovery to form a new mega-studio, built to compete with the tech/entertainment behemoth created by Apple’s recent acquisition of Disney.

The first project on your slate is one you’re very pumped about: Christopher Nolan is readying his next picture. It’s an epic historical drama about the “Bone Wars” — the battle between rival 19th century paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, who ruined their lives trying to outdo each other in the intensely competitive field of fossil hunting. The nonlinear 175-page script is a little mystifying and more dour than you’d like it to be, but it’s Nolan, and he has Christian Bale and Leonardo DiCaprio attached to play Marsh and Cope, so this should be an automatic greenlight. The only issue is the budget — he’s asking for 200 million.

Nolan comes in for a meeting and lays out his vision for the project. He shows you striking photos of the Alberta Badlands, where he intends to shoot much of the film. He talks about recent advances in technology that have made IMAX cameras less cumbersome and noisy. He references a bunch of old movies that you haven’t seen but have definitely heard of.

You tell him how much you love the sound of all this. You then ask him if he’s heard about Konjure, the big new thing in generative cinema. You and your team were presented with a demo of the latest version last week and it really blew you away. It gives so much power to filmmakers — they now have the ability to create anything they can imagine, for practically nothing. You ask Nolan — who, despite his lavish budgets, is known for trying to squeeze the most out of every dollar — if he’s considered using something like this to reduce his VFX spend or cut down on location costs.

He stares at you silently for a few seconds. And then, politely, he explains that filmmaking is about real light entering a real lens pointed at real people in a real place. He reminds you that he’s always favored practical effects over CGI. And he questions whether an AI model trained on mountains of existing footage can ever create something truly original or unique. You tell him that what you’ve seen from the latest technology has put that question to rest — maybe you can have the Konjure guys arrange a personal demo for him. He says he’ll get back to you on that. He stands up, shakes your hand, and leaves.

Twenty minutes later, Nolan’s agent calls you and asks you if you have brain damage. You told him he should think about using AI? Are you stupid? Not only does the guy still shoot on film, he still uses photochemicals to color grade. The big-budget auteurs are all traditionalists. Even James Cameron is refusing to use generative models for anything but the occasional texture or 3D asset in his CGI pipeline — he insists on a level of fine-grained control that the most advanced AI tools can’t offer.

The agent also reminds you that, no matter how cheap it is to create spectacular visuals with a computer, the success of a big-budget film rests upon a global marketing campaign and the presence of real-life movie stars. If you’re spending $100 million on publicity and $50 million on cast, you might as well spend another $50 million on actually shooting the movie and differentiating your product from the growing flood of generated content people can consume online. Though your directive from the corporate higher-ups is to reduce costs as much as possible, you can see the agent’s point. You apologize for offending her biggest client, she commends you for being such a smart and classy exec, you tell her she’s your favorite person in the world, and you hang up. You greenlight The Bone Wars at 200 million. Nolan demands no further meetings with the studio until the film is completed.

It’s a year later, and your job at WarnerUniversal has been eliminated due to post-merger corporate streamlining. You manage to land a coveted EVP position at a hot new indie studio poised to become the next A24. You’re excited to make films that break the mold and push boundaries.

The studio’s mandate is to finance projects with budgets under $15 million. You’ve stayed on top of new developments in generative AI — the tools keep getting more impressive — and you present your colleagues with an idea: what if we try to disrupt the studios from below? It’s now possible to make a low-budget movie boasting all the spectacle of something that used to cost a hundred times more. You know from firsthand experience that the big studios are committed to a business model where spending nine figures on producing and releasing a film is table stakes, and that’s not going to change. Maybe you can eat their lunch.

Your team is intrigued by the idea, but when you discuss it with filmmakers — young filmmakers who came of age in this century — you find surprising resistance. Many of them are philosophically and almost spiritually opposed to generative cinema, for reasons similar to Nolan’s. Some are choosing to side with the labor unions that represent film crews, which are agitating for new contracts that will drastically limit the use of AI to replace real production. And some are simply hesitant to become pariahs in broader film culture — cinephile communities have forcefully rejected the presence of AI in the medium they love, and these are people you need on your side if you want an indie movie to attract an audience.

You do meet one young filmmaker who’s receptive to your ambitions: a kid named Todd. Todd wants to make big sci-fi movies, but all he’s directed so far is a microbudget slasher film. He’s enthusiastic about using whatever tools will let him realize his vision, and he doesn’t really care if Film Twitter hates him. He has a script for a madly ambitious space epic that would cost half a billion dollars to film conventionally; using the latest version of Konjure, all the necessary VFX can be completed for less than $100,000, most of which will go to the artists fine-tuning the instructions fed to the AI. You hire real actors and build a couple of real sets, and make the movie for under $2 million. Todd’s not the greatest writer, and the plot is a little goofy, but you feel like his visual imagination makes up for it — there’s stuff in this movie that you’ve never seen on a screen before.

You show the film to distributors, hoping it will spark a bidding war, but they turn out to be reluctant to make offers. There are no stars in the movie. A wide theatrical release would be risky. Visual spectacle isn’t attracting audiences the way it used to — people are more interested in thrillers and romances featuring big-name actors they know and love. And the story of a film’s production is starting to matter: one of the big hits of the last couple of years was a Tom Cruise movie shot partly in outer space. AI-generated cinema isn’t seen as cinematic. It’s something people can get at home.

You try to sell the movie to streamers, but they pass too, citing the lack of star power. You’re disheartened and a little perplexed, but you’re not giving up. You really believe in the film. You feel it could transform how movies are made, if only people saw it.

With Todd’s approval, you decide to release the film for free on YouTube. You get the trades to write about it, and the company behind Konjure heavily promotes it as a showcase of their product. The film goes moderately viral and gets ten million views, which you’re pretty proud of — ten million people going to see a movie in theaters would mean a gross of over $100 million. You monetized the video with YouTube ads, and you wait to see how much revenue that many views translates to. It ends up being around $30,000. The money goes to your studio to help recoup their production costs. In need of income to pay his rent and maintain his Directors Guild health insurance eligibility, Todd accepts a job directing a low-budget horror film.

At both ends of the business, it’s hard to see generative AI provoking a major transformation in the way Hollywood makes movies. The process of pitching and developing a film could change quite a bit; lookbooks and moodboards might give way to AI-generated trailers and previsualizations of entire sequences. VFX costs will shrink considerably as AI-powered workflows make artists more productive (and eliminate many of their jobs), and the scope of digital effects may expand to contain more aspects of production design, cinematography, and stunt work. But the preferences of high-value talent, the power of labor unions, and the axioms of the studio business model make it unlikely that the industry will fundamentally reshape itself.

So, if we can expect Real Movies to persist in some form within the castle walls, destruction will have to come from the outside. This seems to be the outcome AI boosters are anticipating when they post demos of the latest generative video tools and proclaim that Hollywood is over: people on laptops in their bedrooms will be able to create films so amazing that the industry will simply be wiped out.

There are a few problems with this prediction. One, as alluded to in the Parable of Todd, is the film industry’s robust machinery of distribution and revenue. Thanks to the internet, anything a person makes can be seen everywhere and by everyone. But Hollywood has a unique and powerful capability, honed over many decades: getting large numbers of people to watch stuff, and getting them to pay real money to do it. The biggest Twitch streamer, Kai Cenat, has around 750,000 paying subscribers. The top forty streamers have a combined total of about five million. Netflix has 300 million people paying to watch its shows and films. In a single weekend this month, roughly 30 million people around the world were persuaded to buy tickets to the Minecraft movie and leave their homes to go see it. They were aware of the film’s existence and release date thanks to a marketing campaign that cost as much or more than the 150 million dollar production budget.

By spending monstrous amounts on hiring well-liked celebrities to be in things, and spending amounts ten times greater on promotion, Hollywood studios are able to consistently break through a fractured, chaotic attention economy and get people to come look at what they’ve made, even if the product is of debatable quality. Movies don’t have to go viral to gain an audience; for a major release, positive word-of-mouth is just a force multiplier on the natural power of stars, IP, and aggressive marketing. Without any of these advantages, will the Todds of the world be able to create content so entertaining and so wildly popular that everyone forgets all about Timothée and Zendaya? Even in a potential near-future where movie stars license their likenesses to be used in digitally generated films, would audiences stop wanting a taste of the real thing?

What about the possibility that there will be such a colossal volume of generated content — produced at approximately zero cost, by millions of artists — that the output of the film industry gets drowned out by the newly-empowered masses, and movies lose all cultural currency? We’ve already more or less seen a test of this theory over the last twenty years. The biggest streaming platform isn’t Netflix — it’s YouTube. As long ago as 2014, a survey commissioned by Variety found that the five most well-known celebrities among American teenagers were all YouTubers; more 13 to 17-year-olds had heard of PewDiePie and KSI than Jennifer Lawrence and Seth Rogen. Much of today’s most entertaining and original cinematic work is being shared on TikTok, usually by people who spend no money on what they create and will never see a cent in return. Everyone has a free and infinite river of highly addictive video content within a thumb’s reach during every waking hour. The modern algorithmic feed is to 90s network TV what crack cocaine is to potato chips. And yet people are still watching movies.

Hollywood’s products are no longer the mainstage of culture — arguably, nothing is anymore, other than social media in a broad sense — but with this decentering, we’re seeing something new: the emergence of film as a kind of subculture, offering its members a marker of identity and a sense of community. In a Letterboxd world, taste and discernment start to matter more to the subset of the public still consuming and loving cinema. Not coincidentally, craftsmanship is the main differentiator of movies big and small against the firehose of online video content. The rise of generative cinema will make that distinction all the more meaningful. Films shot with real cameras in the real world may come to be seen as high-value artisanal goods — handmade furniture in a sea of IKEA flatpacks.

Of course, vibrant new spheres of film culture could spring up around the movies people start crafting on their computers. The typical 14-year-old aspiring filmmaker of 2035 might prefer to tinker with a generative video model than go to the trouble of shooting something on their phone. An entire generation of artists will grow up seeing AI as a natural part of their creative toolkit. The line between real and generated cinema may dissolve as these tools seep into every layer of the filmmaking process. Human stars could be supplanted by artificial ones. There’s no way to know how cultural attitudes and audience tastes will shift. What we can predict with some confidence is that the most passionate and dedicated artists will want their work to be seen, and, barring the advent of luxury communism, they’ll want to earn a living from what they create. Unless new business models arise to let filmmakers outside the system command Hollywood-level attention and money, many of them will still strive for a place in the conventional industry.

It’s possible that pondering a hypothetical world of AI-rendered feature films is a little like drawing one of those 1950s futurist illustrations where a “robot vacuum cleaner” is a metal humanoid who pushes a vacuum around — no one was picturing a Roomba. Maybe the true threats to traditional cinema will be new forms of entertainment entirely. A communal viewing experience of the future might center around an always-on live channel of pure AI content continuously dreaming itself into existence, with its creator and viewers collectively in the dark about where the narrative is headed. Open-world games might evolve into rich unbounded universes where characters and stories are no longer limited by pre-defined paths. Virtual partners might become so lifelike and desirable that we enter a perilous dark age of gooning.

It’s hard to imagine, though, that our new diversions will be so enthralling they snuff out the appetite for motion pictures crafted with human intent — the most resilient and adaptive art form of the last hundred years. Since the 1990s, the film industry has weathered the rise of home entertainment, the collapse of mass culture, a limitless deluge of free internet content, smartphones, megabudget videogames, shrinking attention spans, rampant piracy, inept studio heads, multiple strikes, Quibi, and a global pandemic. The fact that it’s still standing — diminished from its past heights, but still a lucrative and powerful business — is a testament not to the acumen of its corporate stewards, but to the enduring value of the medium. Cinema matters to humans. And, we can hope, vice versa.